“Self awareness is an adventure that can be full of surprises”

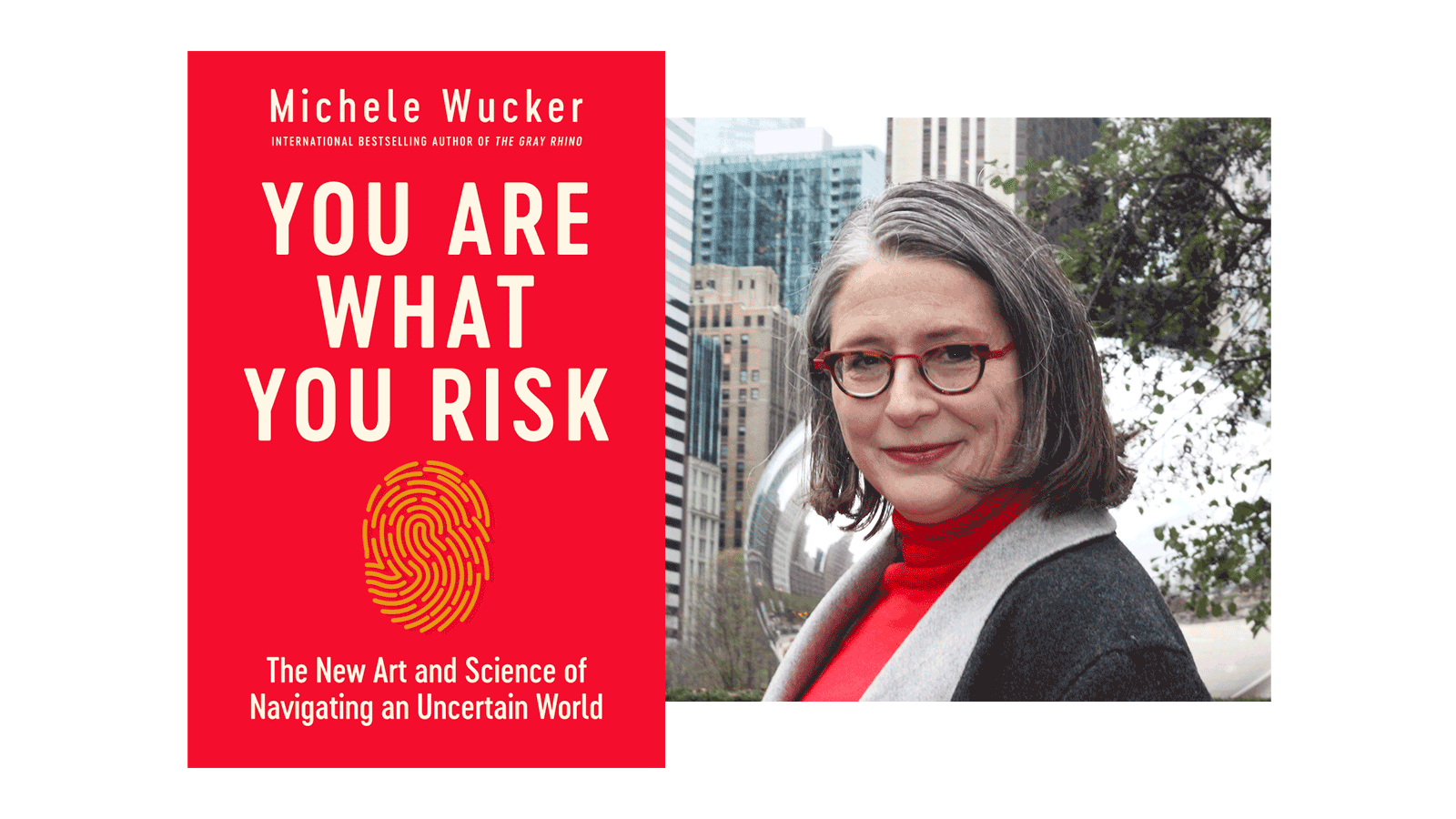

In 2015, she founded Gray Rhino & Company. She is the autor, inter alia, of The Gray Rhino and her new book, YOU ARE WHAT YOU RISK: The New Art and Science of Navigating an Uncertain World (Pegasus Books, April 2021) that takes a much more personal look at what makes each one of us likely to embrace, avoid, or confront the risks we face. It shows how culture, values and societal norms interact with our innate personality, the experiences that shaped us, the social context, and the habits we can develop to make better risk decisions. And it provides a new vocabulary for thinking and talking about risk.

In recent years, your life has been dedicated to the study of global risks, of risk. Why? Is there something magical in human’s relationship with risk and uncertainty?

My interest in risk began when I was writing about capital markets, especially trading of debt and sovereign credit risk in Latin America. The gray rhino metaphor began with a question about why Argentina failed to act in time to keep its credit crisis from spinning out of control. I’ve become interested in the human aspect much more recently, and realized I have been studying risk since before I consciously acknowledged it. The first chapter of my first book, Why the Cocks Fight: Dominicans, Haitians, and the Struggle for Hispaniola, begins with a quote from the anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s famous essay on a Balinese cockfight: “What [the cockfight] says is not merely that risk is exciting, loss depressing, or triumph gratifying, but that it is of these emotions, thus exampled, that society is built and individuals put together.” That book was published in 1999. When I wrote Why the Cocks Fight, I was interested in questions of how society is built, but through a lens of anthropology, history, sociology, political science, economics, and literature. So now I suppose I am filling in the missing piece –risk—that was there all along.

In your book, you say that we are or become or make ourselves according to the risks we take. Are we prisoners of our perception of risk, like the mythological hero Orestes, prisoner of «the Furies»?

People who are not self-aware are prisoners of their perceptions of risk. Each of us has a distinct “risk fingerprint” made up of our innate personality, upbringing and experiences, environment and habits, all of which interact with each other. Being aware of these influences can give us some sense of control over our decisions even though we cannot change our pasts or our personalities. People often ask me if there is an “ideal” risk personality type. There is no ideal type because part of the richness of humanity is the variety of perspectives people bring to life. We need bold risk seekers and adventurers, but we also need the careful, methodical types who keep the lights on and all kinds of personalities in between. People often gravitate to professions that fit their personalities, while others who are unhappy in their jobs may simply be mismatched in a company culture or profession that does not make the most of the strengths of their risk fingerprint.

After reading your last book, I would say that, in a certain way, living is equal to the risks we venture to take, but that taking risks is not taking crazy risks, do you think that taking risks implies an adventure to know ourselves, to know our environment, to know the risk perceptions of others?

Ooh, I love the way you put that. Self awareness is an adventure that can be full of surprises, both things we are not happy to see and others that are delights. Some people are afraid to take this risk, but they are the ones who would benefit most from exploring the uncertain terrain of their own personalities and minds.

Why did you coin the term Grey Rhinoceros a few years ago to refer to risks that, in one way or another, can be anticipated? Wouldn’t risks be more like bulls, which can be fought –if you know–?

I wanted a relatable way to talk about what makes the difference between people who see a danger and act on it, and those who look away or freeze. I pictured a big danger coming right at you and giving a choice of what to do. So the metaphor became rhino because it’s big and its horn is dangerous; and gray because it’s obvious that the rhino is gray. The color also suggests how surprisingly vulnerable humans are to missing what’s right in front of us, since both the “black rhino” and “white rhino” species are gray and neither matches the color of its name. Using an animal followed the tradition of Aesop and other story tellers throughout history.

The personalist thinker E. Mounier said that «the mass of men prefer servitude in security to the risk of independence; to human adventure». Have we forgotten to live, at least in the West, in the sense of taking risks?

It’s not a coincidence that Western societies are full of over-protective helicopter parents at the same time that other people pay lots of money to pursue extreme sports and other dangerous pastimes. I think many Westerners forget how much risk “playing it safe” involves. Much of our risk taking is passive, in the sense of not making the changes we need in fact of a looming danger, as opposed to active risk taking by choice. When we think we’re avoiding risks, it’s not that we’re not taking risks at all but rather that we’re taking different risks. Unfortunately, often doing nothing is the biggest risk of all. We need a mindset shift, to one that weighs the positives and negatives of acting or not acting.

You have written about risks, but have you thought about fears?

Risk is a constant balancing act between hopes and fears. Each one of us approaches risk with a different mix of what we hope versus what we fear, whether we see risk taking as more danger or opportunity or a mix, and how comfortable we are with our hopes and fears. Some of us fear our hopes coming true.

Educating is a risk, insofar as it starts from the freedom of the student, of the other, and this is uncontrollable. Are we educated in this risk, which is to trust in the freedom of the other?

Research by Paul Slovic and others shows that the more control people have over a situation, the less risk they perceive and the more risk they will tolerate. Related to this is the phenomenon that the more people know about a situation, the more comfortable they feel. Knowledge can feel like control. But true knowledge comes from engaging with new and surprising ideas, from being able to hold multiple seemingly contradictory facts in mind, and from wrestling truth away from our internal and societal biases. It’s debatable how much freedom students today have; just look at some of the culture wars on campuses. Many people find it easier to settle comfortably into one ideological clique or the other instead of taking the more difficult, independent path that takes the best and rejects the worst of each clique.

In your book you go into the concept of «risk umbrella». It seems to me a very interesting concept to develop, from the point of view of public policies and the social contract. Is our relationship as citizens with the state and as part of society going to change after this pandemic?

We’ve only begun to grapple with the issues that the pandemic has raised regarding the relationship between citizens and the state. Nevertheless, this is going to be the most important question determining our futures: what kind of risk umbrella will governments, businesses, and civil society provide?. From the first groups of cave people huddled around fires to early city states to nations and today’s multilateral organizations, people have come together to share the responsibilities of fending off risk. The legitimacy of governments depends on how well they protect their citizens, including by inspiring their citizens to do their part to protect each other. We’ve seen a wide range of policy choices and risk messages during the pandemic, involving public health, social safety nets, and other protections. It’s very concerning to see large groups of people refusing to protect themselves and others by rejecting masks and vaccines without legitimate medical reasons to do so. When the virus situation becomes less urgent, we’ll see which changes stay with us, how others evolve, and which ones revert to the mean or even regress.

Do you think that the way to build a global civil society is to assume that it is possible to take some control, at least partially, of some of the global risks?

A sense of human agency -the feeling that each one of us has the power to change- is essential to facing up to global and local risks. When people feel they cannot create a significant impact, they are less likely to do anything at all. Part of the challenge of global risks like climate change and pandemics is that they feel so big that it’s hard to picture how any single person can make a difference. But to solve those challenges, we need as many single individuals as possible to do what they can, both in changing their own behavior and in pushing governments and businesses to do their parts. We need every single government, every single organization, and every single citizen to do their part. That will create a virtuous cycle of positive action.

Finally, you talk a lot about a sense of purpose to put risk in its proper place. Even Dante, had to ask Virgil for guidance to get out of that «dark jungle» (sins, vices) he was in. In our VUCA world, what or who would be our Virgil?

Each person has to find their own Virgil or guiding star, because each of us sees our purpose differently. So there’s no single oracle. Risk is about making choices, which in turn relies on priorities. When your purpose and priorities are clear, you gain clarity when facing difficult choices. In the United States right now, for example, we’re seeing record numbers of people quitting their jobs. Some observers characterize that as “taking bigger risks.” No. I completely disagree. During the pandemic, people have spent more time thinking of what they care about most –in other words, their purpose–and re-ordered their priorities. They’ve also begun to see the risk inherent in sitting in place.

0

0

2

2